最高主宰崇拜

最高主宰崇拜(法语:Culte de l'Être suprême)是法国革命时期罗伯斯庇尔试图建立的一套自然神论[1][2],并试图将其确立为法兰西第一共和国的国教以取代天主教[3][4]。

起源

[编辑]法国大革命为法国带来许多剧烈的变化,但对于一个天主教国家而言最根本的变化便是官方开始抵制宗教。第一个主要而有组织的学派在理性崇拜的保护伞下出现。倡议者多为激进人士如雅克-勒内·埃贝尔以及安托万-弗朗索瓦·莫莫罗,理性崇拜主要是把无神论的观点混合进入人类中心主义哲学的思考中萃取而成。该派别并不敬拜任何神—指导原则是必须投入到理性的抽象概念[5]。

对所有神祇的拒绝震惊了罗伯斯庇尔,并因为其实行中“讽刺的场景”和“狂野的装扮”而更加剧了它对罗伯斯庇尔的冒犯[6]。在1793年末,罗伯斯庇尔对理性崇拜及其支持者发表了强烈的谴责[7],并着手准备自己对于恰当的革命宗教的看法。在1794年5月7日,法国国民公会之前,几乎完全由罗伯斯庇尔构思的“最高主宰崇拜(法语:Le culte de l'Être suprême)”正式公布[8]。

宗教倾向

[编辑]罗伯斯庇尔相信理性只是达到目的的手段,而此非凡的目的就是美德。他试着要突破单纯的自然神论(常被支持者称作伏尔泰思想)来创造新的目的,在他看来,必须对神祇有更合理的投入。最高主宰崇拜的一个主要原则就是信仰单一神的存在以及人类灵魂的不朽[9]。虽然与基督教教义不相抵触,但这些信仰付诸于对罗伯斯庇尔更全面意义上的服务,即是罗伯斯庇尔归功于罗马人与希腊人的公民意识与公共道德[10]。这种美德只能透过对自由与民主积极的忠诚来实现[11]。罗伯斯庇尔认为,相信一位永生的神与更高的道德标准,可以“经常提醒必须实现正义”,并因此对共和社会是至关重要[12]。

革命冲击

[编辑]罗伯斯庇尔使用宗教刊物来公开谴责许多其他阵营的激进团体,并直接或间接地导致了革命的反基督教人士如雅克-勒内·埃贝尔、莫莫罗与阿纳卡西斯·克洛茨的处决[6]。最高主宰崇拜的建立,代表推翻之前颇受官方青睐的大规模去基督教化运动的开始[13]。同时标志了罗伯斯庇尔权力的最高点。虽然理论上他只是公共安全委员会中平等的一员,但罗伯斯庇尔此时在法国境内已经拥有了全国性的声望[14]。

最高主宰崇拜的相关节日

[编辑]

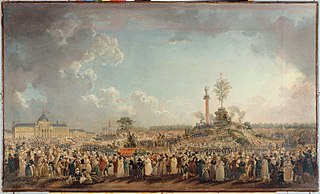

皮埃尔-安托万·德马希作(1794年)

为了开辟新的国教,罗伯斯庇尔宣布共和历二年牧月20日(1794年6月8日)是最高主宰崇拜国家节庆的第一天,且未来的共和假期会在新法国共和历的每一个第十天—休息日(法语:décadi)[8]。每一个地区都必须举行纪念活动,而在巴黎的活动是设计成大规模的型式,由艺术家雅克-路易·大卫所组织,并在战神广场上的人造山周围举行[15]。罗伯斯庇尔承担了所有活动的领导地位,这个强制的行为对很多人来说是十分招摇的[16],这宣告了其新宗教的真理和“社会效用”[17]。

后世影响

[编辑]最高主宰崇拜以及其节庆可以说是促成了热月政变及罗伯斯庇尔的倒台[17]。罗伯斯庇尔于1794年7月28日死于断头台,最高主宰崇拜失去了一切的官方承认,并从此消失在大众的视线中[18]。并在拿破仑一世颁布“共和历10年芽月18日教派法”后正式禁止[19]。

参见

[编辑]注释

[编辑]- ^ a: 法文中的“教派”一字意思是“崇拜的形式”,没有英文中负面或排外的涵义:罗伯斯庇尔打算以此来吸引普遍会众。

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ Jordan, David P. (1985);The Revolutionary Career of Maximilien Robespierre; University of Chicago Press, 1985; ch.11.

- ^ Jordan, pp. 199ff.

- ^ Neely, Sylvia (2008); A Concise History of the French Revolution; Rowman & Littlefield; See p.212 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆): "...(T)he Convention authorized the creation of a civic religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being. On May 7, Robespierre introduced the legislation...."

- ^ Neely, p. 212: "(T)he Convention authorized the creation of a civic religion, the Cult of the Supreme Being. On May 7, Robespierre introduced the legislation...."

- ^ Kennedy, p. 343: "Momoro explained, 'Liberty, reason, truth are only abstract beings. They are not gods....'"

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Kennedy, p. 344.

- ^ Kennedy, p. 344: "Robespierre lashed out against de-Christianization in the Convention...."

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Doyle, p. 276 .

- ^ Kennedy, p. 345.: "Robespierre followed a consistent line of argument...(that) God exists and that the soul is immortal."

- ^ Žižek, p. 111: "I [Robespierre] am talking about the public virtue that worked such prodigies in Greece and Rome, and that should produce far more astonishing ones in republican France...."

- ^ Lyman, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Doyle, p. 276.: "[Robespierre] proclaim[ed] that the French people recognized the existence of a Supreme Being and the immortality of the soul. These principles, declared Robespierre to applause, were a continual reminder of justice, and were therefore social and republican." See also p.262: "[Robespierre] believed that religious faith was indispensable to orderly, civilized society".

- ^ Kennedy, p. 344.: "Robespierre's influence was such that the de-Chistianization movement rapidly slackened...."

- ^ Doyle, p. 277.: "He seemed to be speaking for the Committee of Public Safety more and more, and was certainly better known in the country at large than any of his colleagues. At Orléans, as well as in Paris, the Festival of the Supreme Being took place to cries of "Vive Robespierre"."

- ^ Hanson, p.95:"...[T]he Champ de Mars where David had created an enormous symbolic mountain."

- ^ Doyle, p. 277: "'Look at the bugger,' muttered Thuriot, an old associate of Danton. 'It's not enough for him to be master, he has to be God.'"

- ^ 17.0 17.1 Kennedy, p. 345.

- ^ Neely, p. 230: "The fall of Robespierre brought an end to the Cult of the Supreme Being with which he had been closely identified. The new civic religion... had not had a chance to win many converts."

- ^ Doyle, p. 389.

参考书目

[编辑]- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. Clarendon Press. 1989 [2015-08-24]. ISBN 0-19-822781-7. (原始内容存档于2016-06-17).

- Hanson, Paul R. Historical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. 2004 [2015-08-24]. ISBN 0-8108-5052-4. (原始内容存档于2016-05-27).

- Jordan, David P. The Revolutionary Career of Maximilien Robespierre. University of Chicago Press. 1985 [2015-08-24]. ISBN 0-226-41037-4. (原始内容存档于2016-05-07).

- Kennedy, Emmet. A Cultural History of the French Revolution. Yale University Press. 1989 [2015-08-24]. ISBN 0-300-04426-7. (原始内容存档于2016-05-13).

- Lyman, Richard W.; Spitz, Lewis W. Major Crises in Western Civilization, Vol. 2. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. 1965 [2015-08-24]. (原始内容存档于2016-04-24).

- Neely, Sylvia. A Concise History of the French Revolution. Rowman & Littlefield. 2008 [2015-08-24]. ISBN 0-7425-3411-1. (原始内容存档于2016-05-27).

- Žižek, Slavoj. Robespierre: Virtue and Terror. New York: Verso. 2007 [2015-08-24]. ISBN 1-84467-584-X. (原始内容存档于2016-05-02).

延伸阅读

[编辑]- Rousseau's religious ideas with reference to the religious ideas prominent in the revolution and to their influence on Robespierre and Saint Just(页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆),Elma Gillespie Martin的博士论文(康乃尔大学,1918年)

外部链接

[编辑]- The Supreme Being (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), by Maximilien Robespierre. Source: Internet Modern History Sourcebook, Fordham University, NY.

- Decree on Worship of the Supreme Being (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) Source: Church and state in the modern age: a documentary history; J. F. Maclear, ed.; Oxford Univ. Press, 1999.