乳糜泻

此条目需要扩充。 (2016年12月22日) |

| 乳糜泻 Coeliac disease | |

|---|---|

| 又称 | 麦胶性肠病(gluten enteropathy)、非热带脂肪泻(non-tropical steatorrhea) |

| |

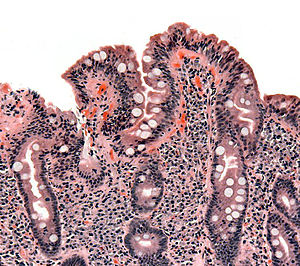

| 乳糜泻患者的小肠绒毛切片,显示小肠绒毛消失,陷窝肥厚且淋巴细胞浸润。 | |

| 读音 | |

| 症状 | 无症状或非特异性症状、腹胀、腹泻、便秘、吸收不良、体重下降、疱疹性皮肤炎[1][2] |

| 并发症 | 缺铁性贫血、骨质疏松症、不孕、癌症、神经系统疾病、其他自身免疫性疾病[3][4][5][6][7] |

| 起病年龄 | 任何年龄[1][8] |

| 病程 | 终身[6] |

| 类型 | autoimmune disease of gastrointestinal tract[*]、麸质相关疾病[*]、疾病 |

| 病因 | 对麸质的反应[9] |

| 诊断方法 | 家族病史、血液抗体检测、肠道活检、基因检测、对移除麸质的反应[10][11] |

| 鉴别诊断 | 炎症性肠病、肠道寄生虫、肠激躁症、囊肿性纤维化[12] |

| 治疗 | 无麸质饮食[13] |

| 患病率 | 约为1/135[14] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 胃肠学、内科学 |

| ICD-11 | DA95 |

| ICD-9-CM | 579.0 |

| OMIM | 609754、612008、612005、612006、607202、611598、612007、612011、612009 |

| DiseasesDB | 2922 |

| MedlinePlus | 000233 |

| eMedicine | 932104、373864 |

| Orphanet | 555 |

乳糜泻(英语:coeliac disease 或 celiac disease)又称麸质敏感性肠病(gluten-sensitive enteropathy)[15],是具有遗传倾向,对含麦胶食物不耐受而导致的肠源性吸收障碍的小肠自身免疫性疾病[10][16]。

典型的症状包含胃肠道症状,像是慢性腹泻、腹胀、吸收不良、降低食欲,以及使孩童生长迟缓。这个病通常发生在六个月大到两岁之间[1]。不典型的症状比较常见,尤其是病人年纪大于两岁时[8][17][18]。肠胃道症状可能轻微或没有表现,另外也可能会有许多症状影响到身体任何部位,或甚至是没有显著症状表现[1]。乳糜泻刚开始是被发现于孩童身上[8][6],但其实任意年纪都可以发病[1][8]。此病常常和其他自身免疫性疾病共病,如1型糖尿病和甲状腺炎等[6]。

机制

[编辑]乳糜泻是因人体不适应麸质进而引发过敏反应的结果。麸质是小麦、大麦及裸麦等谷物含有的一组蛋白质[19][20][21]。一般而言,适量的食用燕麦,若其中无掺混其他含有麸质的谷物,通常不会对儿童患者造成影响[20][22],而食用后会出现乳糜泻问题的几率则可能与于燕麦的品种有关[20][23]。

此症是遗传性疾病[24],患者摄取到麸质后,身体里的异常免疫系统对此产生反应,并可能导致生成数种自身抗体而影响许多不同的器官[25][26]。在小肠中,自身抗体会引发炎症反应,并可能造成生长于小肠内壁的绒毛长度变短(绒毛萎缩)[24][27],而这会影响营养吸收,患者因而经常贫血[24][21]。

诊断

[编辑]确诊通常非常困难,大部分患者在正确诊断前都经历较长的时间[28]。现在有多个检测手段可以使用。患者症状的严重程度可能决定了这些检测的顺序,但如果患者已经在进行无麸质饮食,则所有上述的检测都无效。小肠的损伤通常在饮食中去掉麸质后几周开始恢复,而抗体的水平也在数月后下降。对于那些正在进行无麸质饮食的人群,可能需要在其饮食中每日有一餐加入含麸质的食物,持续六周后再进行检测。[29]

诊断一般是透过血液抗体测试及肠道活体组织切片进行,会用特殊的基因检测作为辅助[10]。不过诊断不容易直接进行[28],多半血液中的抗体检验是阴性的[30][31],而肠道健康的绒毛也只有少许变化[32]。病患在确诊前多半已有严重症状,且持续了几年[33][34]。目前越来越多的确诊案例来自于无症状患者的筛检结果[35]。不过目前尚无足够循证佐证筛检的效果[36]。此病症是由对于麸质蛋白质的永久不耐所造成[10],和更罕见的小麦过敏不同[37]。

治疗

[编辑]目前认为对此病唯一有效的治疗方式是让病患采取严格的终生无麸质饮食。这样可让大多数的患者肠粘膜复元、改善症状并降低产生并发症的风险[13]。如果不加以治疗,此病将可能导致如肠道淋巴瘤等癌症,并会略为增加早期死亡的风险[3]。世界各地罹患此病的人口比率各不相同,从1/300人至1/40不等,平均则是约在1/100至1/170间[14]。据估计,罹有此病者中有高达80%并未被确诊出来,通常是因为他们的胃肠道症状极为轻微或根本没有出现症状,以及因为大众缺乏对于症状和诊断标准的知识所致[5][33][38]。统计上,此病的女性患者较男性略多一些[39]。

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Fasano A. Clinical presentation of celiac disease in the pediatric population. Gastroenterology (Review). April 2005, 128 (4 Suppl 1): S68–73. PMID 15825129. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.015.

- ^ Symptoms & Causes of Celiac Disease | NIDDK. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. June 2016 [24 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-24). (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Lebwohl B, Ludvigsson JF, Green PH. Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMJ (Review). October 2015, 351: h4347. PMC 4596973

. PMID 26438584. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4347.

. PMID 26438584. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4347. Celiac disease occurs in about 1% of the population worldwide, although most people with the condition are undiagnosed. It can cause a wide variety of symptoms, both intestinal and extra-intestinal because it is a systemic autoimmune disease that is triggered by dietary gluten. Patients with coeliac disease are at increased risk of cancer, including a twofold to fourfold increased risk of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and a more than 30-fold increased risk of small intestinal adenocarcinoma, and they have a 1.4-fold increased risk of death.

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Lund2015的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 5.0 5.1 Celiac disease. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines. July 2016 [23 April 2017]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-17).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Ciccocioppo R, Kruzliak P, Cangemi GC, Pohanka M, Betti E, Lauret E, Rodrigo L. The Spectrum of Differences between Childhood and Adulthood Celiac Disease. Nutrients (Review). 22 October 2015, 7 (10): 8733–51. PMC 4632446

. PMID 26506381. doi:10.3390/nu7105426.

. PMID 26506381. doi:10.3390/nu7105426. Several additional studies in extensive series of coeliac patients have clearly shown that TG2A sensitivity varies depending on the severity of duodenal damage, and reaches almost 100% in the presence of complete villous atrophy (more common in children under three years), 70% for subtotal atrophy, and up to 30% when only an increase in IELs is present. (IELs: intraepithelial lymphocytes)

- ^ Lionetti E, Francavilla R, Pavone P, Pavone L, Francavilla T, Pulvirenti A, Giugno R, Ruggieri M. The neurology of coeliac disease in childhood: what is the evidence? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. August 2010, 52 (8): 700–7. PMID 20345955. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2010.03647.x

.

.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, Troncone R, Giersiepen K, Branski D, Catassi C, Lelgeman M, Mäki M, Ribes-Koninckx C, Ventura A, Zimmer KP, (( ESPGHAN Working Group on Coeliac Disease Diagnosis; ESPGHAN Gastroenterology Committee; European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition)). European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease (PDF). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr (Practice Guideline). January 2012, 54 (1): 136–60 [2018-03-29]. PMID 22197856. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e31821a23d0. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2016-04-03).

Since 1990, the understanding of the pathological processes of CD has increased enormously, leading to a change in the clinical paradigm of CD from a chronic, gluten-dependent enteropathy of childhood to a systemic disease with chronic immune features affecting different organ systems. (...) atypical symptoms may be considerably more common than classic symptoms

温哥华格式错误 (帮助) - ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

TovoliMasi2015的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Celiac Disease. NIDDKD. June 2015 [17 March 2016]. (原始内容存档于2016-06-16).

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

VivasVaquero2015的参考文献提供内容 - ^ Ferri, Fred F. Ferri's differential diagnosis : a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders 2nd. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Mosby. 2010: Chapter C. ISBN 978-0323076999.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 See JA, Kaukinen K, Makharia GK, Gibson PR, Murray JA. Practical insights into gluten-free diets. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 2015年10月, 12 (10): 580–91. PMID 26392070. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.156.

A lack of symptoms and/or negative serological markers are not reliable indicators of mucosal response to the diet. Furthermore, up to 30% of patients continue to have gastrointestinal symptoms despite a strict GFD.122,124 If adherence is questioned, a structured interview by a qualified dietitian can help to identify both intentional and inadvertent sources of gluten.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Fasano A, Catassi C. Clinical practice. Celiac disease. The New England Journal of Medicine (Review). December 2012, 367 (25): 2419–26. PMID 23252527. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1113994.

- ^ Nelsen DA Jr. Gluten-sensitive enteropathy (celiac disease): more common than you think. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66(12):2259-2266.

- ^ Uche-Anya E, Lebwohl B. Celiac disease: clinical update. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2021;37(6):619-624. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000785

- ^ Newnham, Evan D. Coeliac disease in the 21st century: Paradigm shifts in the modern age. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2017, 32: 82–85. PMID 28244672. doi:10.1111/jgh.13704.

Presentation of CD with malabsorptive symptoms or malnutrition is now the exception rather than the rule.

- ^ Tonutti E, Bizzaro N. Diagnosis and classification of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. Autoimmun Rev. 2014, 13 (4–5): 472–6. PMID 24440147. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2014.01.043.

- ^ Tovoli F, Masi C, Guidetti E, Negrini G, Paterini P, Bolondi L. Clinical and diagnostic aspects of gluten related disorders. World Journal of Clinical Cases (Review). March 2015, 3 (3): 275–84. PMC 4360499

. PMID 25789300. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i3.275.

. PMID 25789300. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v3.i3.275.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Penagini F, Dilillo D, Meneghin F, Mameli C, Fabiano V, Zuccotti GV. Gluten-free diet in children: an approach to a nutritionally adequate and balanced diet. Nutrients (Review). November 2013, 5 (11): 4553–65. PMC 3847748

. PMID 24253052. doi:10.3390/nu5114553.

. PMID 24253052. doi:10.3390/nu5114553.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Di Sabatino A, Corazza GR. Coeliac disease. Lancet. April 2009, 373 (9673): 1480–93. PMID 19394538. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60254-3.

- ^ Pinto-Sánchez MI, Causada-Calo N, Bercik P, Ford AC, Murray JA, Armstrong D, Semrad C, Kupfer SS, Alaedini A, Moayyedi P, Leffler DA, Verdú EF, Green P. Safety of Adding Oats to a Gluten-Free Diet for Patients With Celiac Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Clinical and Observational Studies (PDF). Gastroenterology. August 2017, 153 (2): 395–409.e3 [2020-02-20]. PMID 28431885. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.04.009. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-01-29).

- ^ Comino I, Moreno M, Sousa C. Role of oats in celiac disease. World Journal of Gastroenterology. November 2015, 21 (41): 11825–31. PMC 4631980

. PMID 26557006. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11825.

. PMID 26557006. doi:10.3748/wjg.v21.i41.11825. It is necessary to consider that oats include many varieties, containing various amino acid sequences and showing different immunoreactivities associated with toxic prolamins. As a result, several studies have shown that the immunogenicity of oats varies depending on the cultivar consumed. Thus, it is essential to thoroughly study the variety of oats used in a food ingredient before including it in a gluten-free diet.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Celiac Disease. NIDDKD. June 2015 [17 March 2016]. (原始内容存档于2016-06-16).

- ^ Lundin KE, Wijmenga C. Coeliac disease and autoimmune disease-genetic overlap and screening. Nature Reviews. Gastroenterology & Hepatology (Review). September 2015, 12 (9): 507–15. PMID 26303674. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.136.

The abnormal immunological response elicited by gluten-derived proteins can lead to the production of several different autoantibodies, which affect different systems.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 86: Recognition and assessment of coeliac disease. London, 2015.

- ^ Vivas S, Vaquero L, Rodríguez-Martín L, Caminero A. Age-related differences in celiac disease: Specific characteristics of adult presentation. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics (Review). November 2015, 6 (4): 207–12. PMC 4635160

. PMID 26558154. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.207.

. PMID 26558154. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v6.i4.207. In addition, the presence of intraepithelial lymphocytosis and/or villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia of small-bowel mucosa, and clinical remission after withdrawal of gluten from the diet, are also used for diagnosis antitransglutaminase antibody (tTGA) titers and the degree of histological lesions inversely correlate with age. Thus, as the age of diagnosis increases antibody titers decrease and histological damage is less marked. It is common to find adults without villous atrophy showing only an inflammatory pattern in duodenal mucosa biopsies: Lymphocytic enteritis (Marsh I) or added crypt hyperplasia (Marsh II)

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Matthias T, Pfeiffer S, Selmi C, Eric Gershwin M. Diagnostic challenges in celiac disease and the role of the tissue transglutaminase-neo-epitope. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol (Review). 2010年4月, 38 (2–3): 298–301. PMID 19629760. doi:10.1007/s12016-009-8160-z.

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Clinical guideline 86: Recognition and assessment of coeliac disease. London, 2015.

- ^ Lewis NR, Scott BB. Systematic review: the use of serology to exclude or diagnose coeliac disease (a comparison of the endomysial and tissue transglutaminase antibody tests). Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. July 2006, 24 (1): 47–54. PMID 16803602. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02967.x.

- ^ Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on the diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Gastroenterology (Review). December 2006, 131 (6): 1981–2002 [2022-07-20]. PMID 17087937. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004. (原始内容存档于2014-03-18).

- ^ Molina-Infante J, Santolaria S, Sanders DS, Fernández-Bañares F. Systematic review: noncoeliac gluten sensitivity. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics (Review). May 2015, 41 (9): 807–20. PMID 25753138. doi:10.1111/apt.13155.

Furthermore, seronegativity is more common in coeliac disease patients without villous atrophy (Marsh 1-2 lesions), but these ‘minor’ forms of coeliac disease may have similar clinical manifestations to those with villous atrophy and may show similar clinical–histological remission with reversal of haematological or biochemical disturbances on a gluten-free diet (GFD).

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Cichewicz AB, Mearns ES, Taylor A, Boulanger T, Gerber M, Leffler DA, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment Patterns in Celiac Disease. Dig Dis Sci (Review). 1 March 2019, 64 (8): 2095–2106. PMID 30820708. doi:10.1007/s10620-019-05528-3.

- ^ Ludvigsson JF, Card T, Ciclitira PJ, Swift GL, Nasr I, Sanders DS, Ciacci C. Support for patients with celiac disease: A literature review. United European Gastroenterology Journal (Review). April 2015, 3 (2): 146–59. PMC 4406900

. PMID 25922674. doi:10.1177/2050640614562599.

. PMID 25922674. doi:10.1177/2050640614562599.

- ^ van Heel DA, West J. Recent advances in coeliac disease. Gut (Review). July 2006, 55 (7): 1037–46. PMC 1856316

. PMID 16766754. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.075119.

. PMID 16766754. doi:10.1136/gut.2005.075119.

- ^ Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Ebell M, Epling JW, Herzstein J, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Phipps MG, Silverstein M, Simon MA, Tseng CW. Screening for Celiac Disease: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. March 2017, 317 (12): 1252–1257. PMID 28350936. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.1462.

- ^ Burkhardt, J. G.; Chapa-Rodriguez, A.; Bahna, S. L. Gluten sensitivities and the allergist: Threshing the grain from the husks. Allergy. July 2018, 73 (7): 1359–1368. PMID 29131356. doi:10.1111/all.13354.

- ^ Lionetti E, Gatti S, Pulvirenti A, Catassi C. Celiac disease from a global perspective. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Gastroenterology (Review). June 2015, 29 (3): 365–79. PMID 26060103. doi:10.1016/j.bpg.2015.05.004.

- ^ Hischenhuber C, Crevel R, Jarry B, Mäki M, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Romano A, Troncone R, Ward R. Review article: safe amounts of gluten for patients with wheat allergy or coeliac disease. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. March 2006, 23 (5): 559–75. PMID 16480395. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02768.x.