家八哥

| 家八哥 | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| 科學分類 | |

| 界: | 動物界 Animalia |

| 門: | 脊索動物門 Chordata |

| 綱: | 鳥綱 Aves |

| 目: | 雀形目 Passeriformes |

| 科: | 椋鳥科 Sturnidae |

| 屬: | 八哥屬 Acridotheres |

| 種: | 家八哥 A. tristis

|

| 二名法 | |

| Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus, 1766)

| |

| 亞種 | |

|

Acridotheres tristis melanosternus | |

| |

| 家八哥的原產地(藍色) | |

| 異名 | |

|

Paradisaea tristis Linnaeus, 1766 | |

家八哥(學名:Acridotheres tristis),俗稱禽吉了,為椋鳥科八哥屬的鳥類,原產於中亞、南亞和中國[2],後來引入美洲、非洲等世界其他地區[3]。

家八哥是雜食性鳥類,喜歡開放的樹林,並且有強烈的領地意識,對城市地區環境適應良好。

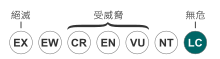

家八哥的分佈範圍增長速度如此之快,以至於在2000年,國際自然保護聯盟物種存續委員會將其列為全球最具入侵物種之一,也是唯一列入《全球最具危害的外來入侵物種100種》中的三種鳥類之一,對生物多樣性、農業和人類利益構成威脅。[4] 特別是在澳洲,該物種對當地生態系統造成嚴重威脅,並於2008年被評為「最重要的害蟲/問題」。[5]

分類

[編輯]1760年,法國動物學家馬蒂蘭·雅克·布里松在他的《鳥類學》(Ornithologie)中描述了家八哥,基於一個他誤認為是在菲律賓採集的標本。他使用了法語名稱Le merle des Philippines 和拉丁名Merula Philippensis。[6] 雖然布里松創造了拉丁名,但它們不符合雙名法,因此不被國際動物命名法委員會承認。[7]

瑞典博物學家卡爾·林奈在1766年更新了他的《自然系統》,為第12版新增了240個由布里松先前描述的物種。[7] 其中之一便是家八哥。林奈提供了簡短的描述,並命名了雙名Paradisea tristis,並引用了布里松的著作。[8] 隨後,模式產地被更正為印度南部的朋迪榭里。[9]種小名tristis 在拉丁語中意為「悲傷」或「憂鬱」。[10] 現今這個物種被歸入法國鳥類學家路易·皮耶·維亞律在1816年引入的八哥屬(Acridotheres)。[11] 屬名Acridotheres 來自希臘語ακριδος (akridos),意為蝗蟲,和θηρας (theras),意為獵手。

- 印度八哥 (A. t. tristis) (林奈,1766年) – 分佈於南哈薩克斯坦、土庫曼、東伊朗至南中國、印度支那、馬來半島和南印度。該亞種也被引入夏威夷和北美。其分佈範圍的西北部群體有時被單獨列為亞種A. t. neumanni,而尼泊爾和緬甸的群體被描述為A. t. tristoides。[13]

- 斯里蘭卡八哥 (A. t. melanosternus)(萊格,1879年) – 斯里蘭卡

斯里蘭卡亞種melanosternus 比印度亞種tristis顏色更深,初級覆羽一半黑一半白,且面頰的黃色斑塊較大。[14][15]

描述

[編輯]

家八哥特徵明顯,棕色的身體、黑色的頭部,眼後有一片裸露的黃色斑塊。喙和腿呈鮮黃色。外側初級羽毛有一個白色斑塊,翅膀下襯羽也是白色的。雌雄鳥相似,通常成對出現。[16] 家八哥遵循格洛格氏定律,來自印度西北部的鳥比來自印度南部的同類顏色更淡。[14][15]

叫聲

[編輯]家八哥的鳴叫聲包括呱呱叫、尖叫、唧唧喳喳、咔嗒聲、口哨和「咆哮」,且常在唱歌時蓬起羽毛、點頭。當附近有掠食者或準備飛翔時,家八哥會尖叫向其配偶或其他鳥類發出警告。[17] 家八哥因其歌唱和「說話」能力而成為受歡迎的籠中鳥。入夜前,家八哥會集體鳴聲,這被稱為「集體噪音」。[18]

形態測量

[編輯]形態測量。[14]

- 身體長度:23厘米(9.1英寸)

| 參數/性別 | 公鳥 | 母鳥 |

|---|---|---|

| 平均體重 (克) | 109.8 | 120–138 |

| 翼弦長 (毫米) | 138–153 | 138–147 |

| 喙長 (毫米) | 25–30 | 25–28 |

| 跗蹠長 (毫米) | 34–42 | 35–41 |

| 尾長 (毫米) | 81–95 | 79–96 |

分佈與棲地

[編輯]

家八哥原產於亞洲,其最初的分佈範圍包括伊朗、巴基斯坦、印度、尼泊爾、不丹、孟加拉和斯里蘭卡、阿富汗、烏茲別克斯坦、塔吉克斯坦、土庫曼斯坦、緬甸、馬來西亞、新加坡、泰國半島、印度支那、日本(包括日本本土和琉球群島)以及中國。[14][19]

家八哥已被引入到世界上許多其他地方,如加拿大、澳洲、以色列、新西蘭、新喀里多尼亞、斐濟、美國(僅南佛羅里達州[20])、南非、哈薩克斯坦、吉爾吉斯斯坦、烏茲別克斯坦、開曼群島、印度洋的島嶼(包括塞舌爾——該物種曾在當地被高成本根除,[21]毛里裘斯、留尼旺、馬達加斯加、馬爾代夫、安達曼-尼科巴群島以及拉克沙群島群島)和大西洋的島嶼(如阿森松島和聖赫勒拿、太平洋島嶼以及塞浦路斯,2022年2月[14][頁碼請求])。家八哥的分佈範圍不斷擴大,至2000年,國際自然保護聯盟物種存續委員會將其列為全球最具危害的入侵物種之一。[4]

它通常棲息於開放的樹林、耕地和人類居住區附近。雖然家八哥是一種適應力強的物種,但在新加坡,由於與入侵的爪哇八哥競爭,其數量異常增多,且被視為害蟲(當地稱其為gembala kerbau,意思是「水牛牧人」)。[22]

家八哥在城市和郊區環境中繁榮生長;例如,在坎培拉,於1968年至1971年間釋放了110隻家八哥。到1991年,坎培拉的家八哥種群密度平均為每平方公里15隻。[23] 僅三年後,另一項研究發現同一地區的平均種群密度達到每平方公里75隻。[24]

家八哥在雪梨和坎培拉的城市和郊區環境中的成功,可能得益於其進化起源;由於家八哥在印度的開放林地中進化,因此它預先適應了有高大垂直結構且地面植被稀少的棲地,[25] 這些特徵與城市街道和自然保護區非常相似。

家八哥(以及歐洲椋鳥、家麻雀和野鴿)對城市建築物造成滋擾;它們的巢穴會堵塞排水溝和排水管,導致建築外部的水損壞。[26]

行為

[編輯]

繁殖

[編輯]

家八哥被認為終生配對。牠們依據所在位置,在一年中的大部分時間內繁殖,通常在樹洞或牆洞中築巢。牠們在喜馬拉雅山脈的海拔0—3,000米(0—9,843英尺)處繁殖。[14]

正常的卵巢大小為4至6顆蛋。蛋的平均大小為30.8乘21.99毫米(11⁄4乘3⁄4英寸)。孵卵期為17至18天,雛鳥離巢期為22至24天。[14]噪鵑有時會對這種鳥類進行巢寄生。[27] 家八哥使用的築巢材料包括樹枝、根、粗麻和垃圾。家八哥已知會使用紙巾、錫箔和脫落的蛇皮來築巢。[14]

在繁殖季節,1978年4月至6月普納的家八哥日間活動時間分配如下:築巢活動佔42%,環境掃描佔28%,移動佔12%,覓食佔4%,發聲佔7%,梳理相關活動、互動及其他活動佔7%。[28]

家八哥會使用啄木鳥、鸚鵡等的巢,並容易接受巢箱;有紀錄顯示家八哥會將之前巢中的雛鳥用喙叼走,有時甚至不會使用空置的巢箱。這種侵略性行為促成了其作為入侵物種的成功。[29]

還有一些證據表明,在引入的環境中,家八哥更傾向於選擇在人為改造的結構中築巢,而不是在自然樹洞中,這與本地鳥種相比尤其明顯。[30]

食物與覓食

[編輯]像大多數椋鳥一樣,家八哥是雜食性鳥類。牠們以昆蟲、蛆、蚯蚓、蜘蛛、甲殼類、爬行動物、小型哺乳動物、種子、穀物、水果、花蜜和花瓣,以及人類居住區丟棄的廢棄物為食。[31] 牠們會在草地上覓食昆蟲,特別是蚱蜢,這也是其屬名Acridotheres「蚱蜢獵手」的由來。不過,牠們吃多種昆蟲,大多數是從地面上撿來的。[14][32] 牠們還是像Salmalia和Erythrina這類花卉的傳粉者。牠們步行在地面上,有時跳躍,並抓住被放牧的牛或燃燒的草地驚動的昆蟲覓食。[14] 牠們會捕食其他鳥類的蛋和幼鳥,如夏威夷棕櫚雀(Loxops coccineus)。[31] 有時候,牠們甚至會在淺水中涉水捕魚。[31] 由於居住在靠近人類建築物的棲地,家八哥也會出現在路邊以車禍的動物屍體為食。[33]

棲息行為

[編輯]家八哥全年都會集體棲息,通常會與叢林八哥、粉紅椋鳥、家鴉、叢林鴉、牛背鷺、紅領綠鸚鵡等鳥類混群棲息。棲息的群體規模從少於一百隻到數千隻不等。[34][35] 家八哥到達棲地的時間從日落前開始,並在日落後結束。牠們在日出前離開。到達和離開的時間及時間跨度、最終在棲地安定的時間、集體睡眠的持續時間、群體大小和數量會隨季節變化。[18][36][37]

集體棲息的功能是同步各種社交活動,避免掠食者,交換食物來源的信息。[38]

集體表現(棲息前和棲息後)包括空中機動飛行,這些行為在繁殖季前(11月至3月)會表現出來。推測這種行為與配對形成有關。[39]

入侵物種

[編輯]國際自然保護聯盟(IUCN)將家八哥列為全球世界百大外來入侵種中的三種鳥類之一[4](另外兩種是黑喉紅臀鵯和歐洲椋鳥)。 法國人在18世紀從朋迪榭里引入家八哥到毛里裘斯,旨在控制昆蟲,甚至對任何迫害這種鳥類的人處以罰款。[40] 此後,家八哥被廣泛引入其他地方,包括東南亞鄰近地區、馬達加斯加、[41]中東、南非、美國、阿根廷、德國、西班牙和葡萄牙、[42]英國、澳洲、新西蘭及印度洋和太平洋的多個島嶼,其中在斐濟和夏威夷的種群尤為顯著。[2][43]

家八哥在南非、北美、中東、澳洲、新西蘭及多個太平洋島嶼被視為害鳥。它在澳洲尤為棘手。[44] 多種方法已被嘗試以控制家八哥的數量並保護本地物種。[45]

澳洲

[編輯]

在澳洲,家八哥是一種入侵物種和害鳥。在整個澳洲東岸的城市地區,家八哥經常是主要鳥類。2008年,在一次民意投票中,家八哥被評為澳洲的「最重要的害蟲/問題」。由於其數量龐大及拾荒行為,它們被稱為「會飛的老鼠」,也被稱為「天空中的海蟾蜍」。[5] 然而,關於它對本地物種的影響程度,科學界尚無一致共識。[46][47]

家八哥首次於1863年至1872年間被引入澳洲維多利亞州,用來控制墨爾本市場花園中的昆蟲。大約同時期,該鳥可能已經擴散到新南威爾斯(目前家八哥在該州最為多見),但相關記錄不詳。[48] 之後,家八哥被引入昆士蘭以捕食蚱蜢和甘蔗甲蟲。目前澳洲的家八哥種群主要集中在東部沿海地區,特別是雪梨及其周邊郊區,[49] 在維多利亞州分佈較稀疏,在昆士蘭則有一些孤立的社區。[50] 2009年期間,新南威爾斯的幾個市政委員會開始嘗試捕捉家八哥,以減少其數量。[51]

家八哥可以在各種氣溫範圍內生存和繁殖,從坎培拉的寒冷冬季到凱恩斯的熱帶氣候不等。已發現其自我維持的種群存在於月平均最高氣溫不低於23.2 °C(73.8 °F)和月平均最低氣溫不低於−0.4 °C(31.3 °F)的地區,這意味着家八哥可能會從雪梨向北擴展至凱恩斯的東海岸,向西擴展至阿德萊德的南海岸,但不會擴展至塔斯馬尼亞、達爾文或內陸乾旱地區。[50]

歐洲

[編輯]2019年,家八哥被列入歐盟關注的入侵外來物種名單。[52] 它們已在西班牙和葡萄牙建立了種群,[53] 並被引入法國,偶爾在當地繁殖。[54]

新西蘭

[編輯]家八哥於19世紀70年代被引入到新西蘭的北島和南島。然而,南島較涼爽的夏季氣溫似乎阻礙了當地種群的繁殖成功率,這導致該物種無法繁衍,到19世紀90年代時,家八哥在南島基本上已經不存在。與此相對,北島的種群能夠成功繁殖,現在大部分的北島都有家八哥分佈。然而,北島南部地區的涼爽夏季氣溫,與南島相似,亦阻止了大型家八哥種群的建立。[55][33] 自1950年代以來,家八哥已向北擴展,現在超出了懷卡托地區,[56] 主要成功的種群集中於低緯度地區,因為當地氣候較為溫暖。[56] 目前,家八哥在低緯度地區尤其常見,特別是在北地地區,[33] 但在旺格努伊以南的地區則較為罕見。[57]

南非

[編輯]在南非,家八哥於1902年逃入野外後變得非常普遍,其分佈範圍在有人類活動或人類干擾較多的地區更廣。[58] 這種鳥類因其強烈的領地意識,常被認為是害鳥,會趕走其他鳥類並殺死牠們的幼鳥。在南非,家八哥被視為主要的害鳥,對自然棲地造成擾亂;因此,它已被宣佈為入侵物種,[59] 需要進行控制。

形態學研究顯示,空間排序過程影響了A. tristis 在南非的擴散範圍。[60] 與擴散相關的性狀與距離種群核心的距離顯著相關,並且表現出強烈的兩性異形,暗示存在性別偏向的擴散。形態變異在雌鳥的翅膀和頭部特徵中尤為顯著,這表明雌鳥是主要的擴散性別。相比之下,與擴散無關的性狀,如與覓食相關的性狀,未顯示出空間排序的跡象,但受植被和城市化強度等環境變量顯著影響。

美國

[編輯]在夏威夷,家八哥正與許多本地鳥類競爭食物和築巢地點。[61]

為了研究A. tristis 的入侵遺傳學及景觀尺度動態,科學家最近使用次世代定序(NGS)方法開發了16個多態性核微衛星標記。[62]

對生態系統與人類的影響

[編輯]對本地鳥類的威脅

[編輯]家八哥是一種空洞築巢的鳥類,即牠們在天然的樹洞或建築物上的人工空洞中(例如凹陷的窗臺或低矮的簷篷)築巢繁殖。[63] 與本地空洞築巢鳥類相比,家八哥極具攻擊性,繁殖期的雄鳥會積極保護其領域,範圍可達0.83公頃(但在人口密集的城市環境中,雄鳥通常只保護巢穴周圍的區域)。[64]

這種攻擊性使得家八哥能夠取代許多本地空洞築巢鳥類的繁殖配對,從而降低了它們的繁殖成功率。在澳洲,家八哥甚至能將像粉紅鳳頭鸚鵡這樣的大型本地鳥類趕出它們的巢穴。

此外,家八哥還會同時維護多達兩個棲地;一個是靠近繁殖地的臨時夏季棲地(在夏季,這是一個雄鳥社群集體過夜的地方,這也是攻擊性最強的時期),另一個是全年性的永久棲地,雌鳥在那裏孵蛋過夜。無論雄鳥還是雌鳥,都會激烈保護這兩個棲地,進一步排擠本地鳥類。[64]

對農作物和牧場的威脅

[編輯]家八哥主要以地棲昆蟲、熱帶水果(如葡萄、李子及某些莓果)以及城市區域的廢棄人類食物為食。[65] 它對澳洲的藍莓作物構成嚴重威脅,但其主要威脅仍是本地鳥類。[66]

在夏威夷,家八哥最初被引入是為了控制甘蔗作物中的粘蟲和切根蟲,但它反而促進了馬纓丹這種頑固雜草在島嶼的開放草原上的蔓延。[67] 2004年一項夏威夷農業局的調查顯示,家八哥在水果產業中被列為第四大鳥類害蟲,並在所有鳥類害蟲投訴中排名第六。[68]

家八哥對成熟水果造成的破壞相當大,尤其是葡萄,也包括無花果、蘋果、梨、草莓、藍莓、番石榴、芒果和麵包果。鄰近城市地區的穀物作物,如玉米、小麥和稻米也易受其害。與人類共同棲息和築巢會帶來美觀和健康方面的問題。已知家八哥攜帶禽瘧疾及如Ornithonyssus bursia蟎這樣的外來寄生蟲,這些寄生蟲會引發人類皮膚炎。家八哥還有助於傳播農業雜草的種子,例如馬纓丹,由於其侵入性,被列為「國家重大雜草」。家八哥經常被觀察到奪取巢穴和空洞,摧毀本地鳥類的蛋,並殺死它們的幼鳥,包括海鳥和鸚鵡。還有證據顯示家八哥曾殺死過像老鼠、松鼠和負鼠這樣的小型陸地哺乳動物,但這些情況仍需要進一步研究。[69]

控制

[編輯]此章節需要擴充。 (2022年1月1日) |

家八哥作為主要的農業害鳥,並在非原產國家對本地物種構成威脅,因此受到多種因素的控制。控制家八哥的方法包括將其殺死或驅趕。目前使用的控制手段有毒藥、[56] 槍擊、[56] 籠式陷阱[56] 和驅鳥設備。[56]

文化中的家八哥

[編輯]在梵文文學中,家八哥有許多名稱,大多描述其外觀或行為。除了saarika之外,家八哥的名稱還包括kalahapriya,意思是「喜歡爭吵的人」,指的是這種鳥愛爭吵的天性;chitranetra,意為「畫眼」;peetanetra(黃眼者)以及peetapaad(黃腳者)。[70]

圖庫

[編輯]參考文獻

[編輯]- ^ Acridotheres tristis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2012. [26 November 2013].

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Common Myna. [December 23, 2007]. (原始內容存檔於2013-01-20).

- ^ Common Myna - Audubon Field Guide. Audubon. 2014-11-13 [2 March 2016]. (原始內容存檔於2019-10-25).

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Lowe S., Browne M., Boudjelas S. and de Poorter M. (2000, updated 2004). 100 of the World's Worst Invasive Alien Species: A selection from the Global Invasive Species Database 互聯網檔案館的存檔,存檔日期2017-03-16.. The Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG), a specialist group of the Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the World Conservation Union (IUCN), Auckland.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 ABC Wildwatch. Abc.net.au. [2012-08-07]. (原始內容存檔於2012-11-09).

- ^ Brisson, Mathurin Jacques. Ornithologie, ou, Méthode contenant la division des oiseaux en ordres, sections, genres, especes & leurs variétés 2. Paris: Jean-Baptiste Bauche. 1760: 278–280, Plate 26 fig 1 (法語及拉丁語). The two stars (**) at the start of the section indicates that Brisson based his description on the examination of a specimen.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Allen, J.A. Collation of Brisson's genera of birds with those of Linnaeus. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 1910, 28: 317–335. hdl:2246/678.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl. Systema naturae : per regna tria natura, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis 1 12th. Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. 1766: 167 (拉丁語).

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Greenway, James C. Jr (編). Check-list of birds of the world 15. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. 1962: 112–113.

- ^ Jobling, J.A. del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J.; Christie, D.A.; de Juana, E. , 編. Key to Scientific Names in Ornithology. Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions. 2018 [11 May 2018].

- ^ Vieillot, Louis Pierre. Analyse d'une Nouvelle Ornithologie Élémentaire. Paris: Deterville/self. 1816: 42 (法語).

- ^ Gill, Frank; Donsker, David (編). Nuthatches, Wallcreeper, treecreepers, mockingbirds, starlings, oxpeckers. World Bird List Version 8.1. International Ornithologists' Union. 2018 [11 May 2018].

- ^ Kannan, Ragupathy; James, Douglas A., Billerman, Shawn M.; Keeney, Brooke K.; Rodewald, Paul G.; Schulenberg, Thomas S. , 編, Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis), Birds of the World (Cornell Lab of Ornithology), 2020-03-04 [2021-08-23], doi:10.2173/bow.commyn.01 (英語)

- ^ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 Ali, Salim; Ripley, S. Dillon. Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan, Volume 5 2 (paperback). India: Oxford University Press. 2001: 278. ISBN 978-0-19-565938-2.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderton, John C. Birds of South Asia - The Ripley Guide (volume 2). Smithsonian Institution, Washington & Lynx edicions, Barcelona. 2005: 584, 683. ISBN 978-84-87334-66-5.

- ^ Rasmussen, PC & JC Anderton. Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Vol 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. 2005: 584.

- ^ Griffin, Andrea S. Social learning in Indian mynahs, Acridotheres tristis: the role of distress calls.. Animal Behaviour. 2008, 75 (1): 79–89. S2CID 53184596. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2007.04.008.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Mahabal, Anil; Vaidya, V.G. Diurnal rhythms and seasonal changes in the roosting behaviour of Indian Myna Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus). Proceedings of Indian Academy of Sciences (Animal Science). 1989, 98 (3): 199–209 [22 January 2011]. S2CID 129156314. doi:10.1007/BF03179646.

- ^ Common Myna. [December 23, 2007].

- ^ Common Myna – Audubon Field Guide. Audubon. 2014-11-13 [2 March 2016].

- ^ Evans, Thomas; Angulo, Elena; Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Turbelin, Anna; Courchamp, Franck. Global economic costs of alien birds. PLOS ONE. 2023, 18 (10): e0292854. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1892854E. PMC 10584179

. PMID 37851652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0292854

. PMID 37851652. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0292854  .

.

- ^ Ubiquitous Javan Myna. Bird Ecology Study Group, Nature Society (Singapore). Besgroup.blogspot.com. [October 25, 2007].

- ^ Pell & Tidemann 1997a,第141–149頁.

- ^ Pell & Tidemann 1997a,第146頁.

- ^ Pell & Tidemann 1997a,第141頁.

- ^ Bomford & Sinclair 2002,第35頁.

- ^ Choudhury A. Common Myna feeding a fledgling koel. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1998, 95 (1): 115.

- ^ Mahabal, Anil. Activity-time budget of Indian Myna Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus) during the breeding season. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1991, 90 (1): 96–97 [22 January 2011].

- ^ Pande, Satish; Tambe, Saleel; Clement, Francis M; Sant, Niranjan. Birds of Western Ghats, Kokan and Malabar (including birds of Goa). Mumbai: Bombay Natural History Society & Oxford University Press. 2003: 312, 377. ISBN 978-0-19-566878-0.

- ^ Lowe, Katie A.; Taylor, Charlotte E.; Major, Richard E. Do Common Mynas significantly compete with native birds in urban environments?. Journal of Ornithology. 2011-10-01, 152 (4): 909–921. ISSN 0021-8375. S2CID 3153551. doi:10.1007/s10336-011-0674-5 (英語).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Acridotheres tristis (Common myna). Animal Diversity Web.

- ^ Mathew, DN; Narendran, TC; Zacharias, VJ. A comparative study of the feeding habits of certain species of Indian birds affecting agriculture. J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 1978, 75 (4): 1178–1197.

- ^ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Taonga, New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu. Starlings and mynas. teara.govt.nz.

- ^ Mahabal, Anil; Bastawade, D.B. Mixed roosting associates of Indian Myna Acridotheres tristis in Pune city, India. Pavo. 1991, 29 (1 & 2): 23–32 [22 January 2011].

- ^ Mahabal, Anil. Diurnal intra- and inter-specific assemblages of Indian Mynas. Biovigyanam. 1992, 18 (2): 116–118 [22 January 2011].

- ^ Mahabal, Anil; Bastawade, D.B.; Vaidya, V.G. Spatial and temporal fluctuations in the population of Common Myna Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus) in and around an Indian City. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1990, 87 (3): 392–398 [22 January 2011].

- ^ Mahabal, Anil. Seasonal changes in the flocking behaviour of Indian Myna Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus). Biovigyanam. 1993, 19 (1 & 2): 55–64 [22 January 2011].

- ^ Mahabal, Anil. Communal roosting in Common Mynas and its functional significance. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 1997, 94 (2): 342–349 [22 January 2011].

- ^ Mahabal, Anil. Communal display behaviour of Indian Myna Acridotheres tristis (Linnaeus). Pavo. 1993, 31 (1&2): 45–54.

- ^ Palmer; Bradshaw (編). The Mauritius Register: Historical, official and Commercial, corrected to the 30th June 1859.. Mauritius: L. Channell. 1859: 77.

- ^ Wilme, Lucienne. Composition and characteristics of bird communities in Madagascar (PDF). Biogéographie de Madagascar. 1996: 349–362.

- ^ Saavedra et al. 2015,第121–127頁.

- ^ Long, John L. (1981). Introduced Birds of the World. Agricultural Protection Board of Western Australia, 21-493

- ^ Grarock, Kate; Tidemann, Christopher R.; Wood, Jeffrey; Lindenmayer, David B. Sueur, Cédric , 編. Is It Benign or Is It a Pariah? Empirical Evidence for the Impact of the Common Myna (Acridotheres tristis) on Australian Birds. PLOS ONE. 2012-07-11, 7 (7): e40622. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...740622G. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3394764

. PMID 22808210. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040622

. PMID 22808210. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0040622  (英語).

(英語).

- ^ Cruz & Reynolds 2019,第302-308頁.

- ^ Sol, D.; Bartomeus, I.; Griffin, A. S. The paradox of invasion in birds: Competitive superiority or ecological opportunism?. Oecologia. 2012, 169 (2): 553–564. Bibcode:2012Oecol.169..553S. PMID 22139450. S2CID 253972110. doi:10.1007/s00442-011-2203-x.

- ^ Grarock et al (2013) Are invasive species drivers of native species decline or passengers of habitat modification? A case study of the impact of the common myna (Acridotheres tristis) on Australian bird species. Austral Ecology.

- ^ Hone, J. Introduction and Spread of the Common Myna in New South Wales (PDF). Emu. 1978, 78 (4): 227. Bibcode:1978EmuAO..78..227H. doi:10.1071/MU9780227.

- ^ Old, Julie M.; Spencer, Ricky-John; Wolfenden, Jack. The Common Myna (Sturnus tristis) in urban, rural and semi-rural areas in Greater Sydney and its surrounds. Emu - Austral Ornithology. 2014, 114 (3): 241–248. Bibcode:2014EmuAO.114..241O. S2CID 84731024. doi:10.1071/MU13029.

- ^ 50.0 50.1 Martin 1996,第169–170頁.

- ^ Campion, Vikki. Councils assessing backyard traps to catch Indian Mynah birds. The Daily Telegraph. Australia. 2009-05-12 [2012-08-07]. (原始內容存檔於2012-10-01).

- ^ List of Invasive Alien Species of Union concern – Environment – European Commission. ec.europa.eu. 19 December 2023.

- ^ Saavedra, Serguei. A survey of recent introduction events, spread and mitigation efforts of mynas (Acridotheres sp.) in Spain and Portugal.. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation. 2015, 38: 121–127. doi:10.32800/abc.2015.38.0121

. hdl:10261/120917

. hdl:10261/120917  .

.

- ^ Dubois P.J. & J.M. Cugnasse (2015).- Les populations d'oiseaux allochtones en France en 2014 (3e enquête nationale). Ornithos : 22-2 : 72–91.

- ^ 9. – Introduced land birds – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand.

- ^ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 Pest control hub – Northland Regional Council. www.nrc.govt.nz.

- ^ Myna information: study tracks history of pesky birds in New Zealand – The University of Auckland. www.auckland.ac.nz.

- ^ Peacock, Derick S.; van Rensburg, Berndt J. & Robertson, Mark P. The distribution and spread of the invasive alien Common Myna, Acridotheres tristis L. (Aves: Sturnidae), in southern Africa. South African Journal of Science. 2007, 103: 465–473.[永久失效連結]

- ^ National List of Invasive Bird Species (PDF). Government Gazette. 29 July 2016 [11 February 2021].[永久失效連結]

- ^ Berthouly-Salazar, C.; van Rensburg, B.J.; van Vuuren, B.J.; Hui, C. Spatial sorting drives morphological variation in the invasive bird, Acridotheres tristis. PLOS ONE. 2012, 7 (5): e38145. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738145B. PMC 3364963

. PMID 22693591. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038145

. PMID 22693591. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038145  .

.

- ^ COMMON MYNA Acridotheres tristis (PDF). Hbs.bishopmuseum.org. [18 March 2022].

No introduced species in Hawaii has elicited so much opinion as the Common Myna, perhaps in part due to its intelligence and amusing anthropomorphic qualities. Although they were thought to be of "great value to the aviculturist" in Hawaii for controlling pests (Bryan 1937b), it was also generally vilified for its noisy habits, "quarrelsome" and opportunistic nature, disturbance to domestic pigeons, fruit-eating and nest-robbing habits, and the possibility of its adversely affecting native bird populations (e.g., Finsch 1880; Wilson 1890a; Rothschild 1900; Perkins 1901, in Evenhuis 2007:75)

- ^ Berthouly-Salazar, C.; Cassey, P.; van Vuuren, B.J.; van Rensburg, B.J.; Hui, C.; le Roux, J.J. Development and characterization of 13 new, and cross amplification of 3, polymorphic nuclear microsatellite loci in the Common myna (Acridotheres tristis). Conservation Genetics Resources. 2012, 4 (3): 621–624. Bibcode:2012ConGR...4..621B. S2CID 16022159. doi:10.1007/s12686-012-9607-8. hdl:10019.1/113194

.

.

- ^ Bomford & Sinclair 2002,第34頁.

- ^ 64.0 64.1 Pell & Tidemann 1997a,第148頁.

- ^ Pell & Tidemann 1997a,第147頁.

- ^ Bomford & Sinclair 2002,第30頁.

- ^ Pimentel, D.; Lori Lach; Rodolfo Zuniga; Doug Morrison. Environmental and Economic Costs of Nonindigenous Species in the United States. BioScience. January 2000, 50 (1): 53–56. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2000)050[0053:EAECON]2.3.CO;2

.

.

- ^ Koopman, ME & W C Pitt. Crop diversification leads to diverse bird problems in Hawaiian agriculture (PDF). Human–Wildlife Conflicts. 2007, 1 (2): 235–243 [2011-01-26]. (原始內容 (PDF)存檔於2009-01-10).

- ^ Myna birds. 2018.

- ^ Dave, K. N. Birds in Sanskrit Literature revised. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Private Ltd. 2005: 468, 516. ISBN 978-81-208-1842-2.

| 這是一篇與雀形目相關的小作品。您可以透過編輯或修訂擴充其內容。 |